Client Stories are Data with Soul

Lived Experience, AI, and Emotional Support

Statistics tell us that something is happening. Stories tell us how it feels.

Much of my research begins not with abstract models or policy frameworks, but with how people actually live with technology in everyday life. This means starting from experience — from the ways individuals incorporate digital systems into moments of uncertainty, vulnerability, and reflection — rather than from how those systems are imagined in product design, regulation, or theory.

Increasingly, adults experiencing anxiety, low mood, loneliness, or emotional overwhelm are turning to generative AI systems for emotional support. This is not typically framed by users as a replacement for therapy, nor as a rejection of human relationships. Instead, it emerges in moments when human support feels unavailable, risky, or too exposed — when people want to articulate thoughts without consequence, judgement, or obligation.

People consistently describe turning to AI at points of uncertainty rather than crisis: when I don’t know what to do; when I don’t want to burden anyone; when I’m too embarrassed to ask; when I’m afraid of being judged; when I just need to think out loud. For some, the appeal lies in the absence of social consequence. For others, it is the immediacy, privacy, or perceived impartiality of the interaction — the sense that one can articulate thoughts without worrying how they will land, or what they will require of another person.

Research in psychology and human–computer interaction suggests that people turn to non-human sources of support during periods of cognitive overload or emotional ambiguity. Generative AI is increasingly used in these moments, not for advice but as a temporary cognitive and emotional scaffold — supporting organisation, rehearsal, and sense-making without the demands or risks of social interaction.

What emerges is not technological naïvety but contextual coping shaped by unequal access to time, care, and emotionally safe interaction. Research on stigma, help-seeking, and social risk shows that people often avoid interpersonal disclosure when judgement, obligation, or relational consequence feels likely. In this context, AI systems are valued not for their insight, but for their availability, predictability, and lack of social repercussion — qualities that reduce perceived interpersonal risk even as users remain aware of the system’s limitations.

Why this is ethically and psychologically significant

Unlike earlier digital mental-health tools or app-based interventions, generative AI systems are responsive, adaptive, and linguistically fluent. They mirror tone, reflect affect, and adjust language in ways that can simulate attentiveness or understanding. As researchers in human–computer interaction and affective computing have long noted (e.g. Sherry Turkle, Rosalind Picard, Byron Reeves & Clifford Nass), people readily attribute social and emotional meaning to systems that appear responsive — even when they know those systems are not sentient.

What is distinctive about contemporary generative AI is not simply its sophistication, but its availability at scale, its integration into everyday platforms, and its positioning as neutral, helpful, or supportive. For some users, this creates relief or containment; for others, it introduces uncertainty around authority, reliability, and emotional dependency.

Importantly, different AI models produce meaningfully different experiences. Variations in tone, framing, refusal style, and responsiveness shape whether an interaction feels containing, evasive, judgemental, or misleading. This has direct implications for trust, reliance, and psychological impact — yet remains largely unexamined in current governance frameworks.

Situating the work

This research sits at the intersection of:

- Human–technology interaction and social computing (e.g. Sherry Turkle, Lucy Suchman)

- Affective computing and emotional AI (Rosalind Picard)

- Addiction, compulsion, and digital design (Natasha Dow Schüll)

- AI ethics, power, and political economy (Kate Crawford, Joanna Bryson, Carissa Véliz)

- AI governance and lived impact (e.g. Oxford Internet Institute, Institute for Ethics in AI, AI Now Institute)

What distinguishes this work is its focus on inner life — on how technologies shape not just behaviour or outcomes, but emotional regulation, self-understanding, and relational expectations.

Implications

- For clinical practice, AI use may shape how distress is articulated and regulated before therapy begins.

- For policy and regulation, emotionally responsive AI raises questions of consent, accountability, and substitution for care.

- For technology design, it highlights the psychological impact of tone, framing, availability, and authority — beyond accuracy or bias.

- For public life, it prompts a deeper question: how technologies are reshaping the conditions under which people feel held, heard, and able to think.

Orientation

At its core, this work is guided by a simple concern:

- when technologies begin to feel supportive, responsive, or relational

- it becomes necessary to examine not only what they can do

- but how they are interpreted, relied upon, and integrated into everyday life

- and what they come to mean for emotional regulation, care, and self-understanding

The aim is neither to pathologise these practices nor to celebrate them uncritically, but to make visible a largely unexamined dimension of contemporary emotional life — one that is already reshaping how care, responsibility, and self-understanding are organised. This shift demands attention now, before it hardens into an unexamined norm.

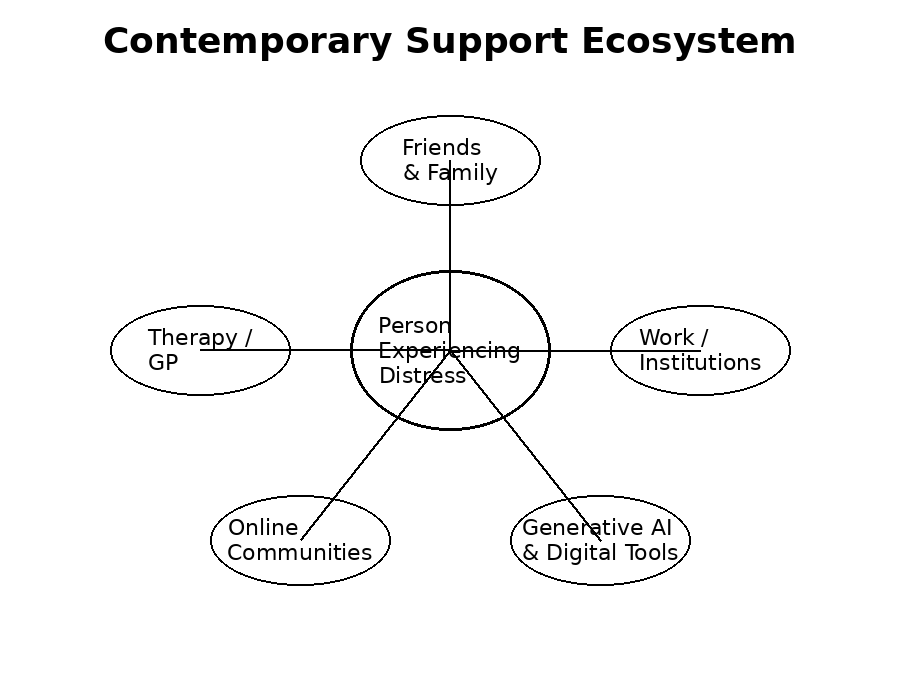

Figure X. A conceptual model of the contemporary support ecology surrounding an individual experiencing psychological distress, illustrating multiple formal, informal, and digitally mediated sources of support.